In 1848, the first Chinese immigrants arrived in California and after a few years thousands more came. According to Angel Island Conservancy, they were lured by the promise of Gam Sann, known as “Gold Mountain.” Quickly, discriminatory legislation forced them out of the gold fields and into low-paying jobs. These jobs included laying the tracks for the Central Pacific Railroad. They reclaimed swamp land in the Sacramento delta, developed shrimp and abalone fisheries, and provided cheap labor when U.S. citizens or other groups did not want to do it. By the 1870s, the economy downturned. This resulted in unemployment problems and led to politically motivated arguments against immigrants who would work for low wages. Due to this, the states began to pass immigration laws. The federal government also asserted its authority in controlling immigration by passing the first immigration law in 1882, specifically targeting Chinese immigrants.

China Cove and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

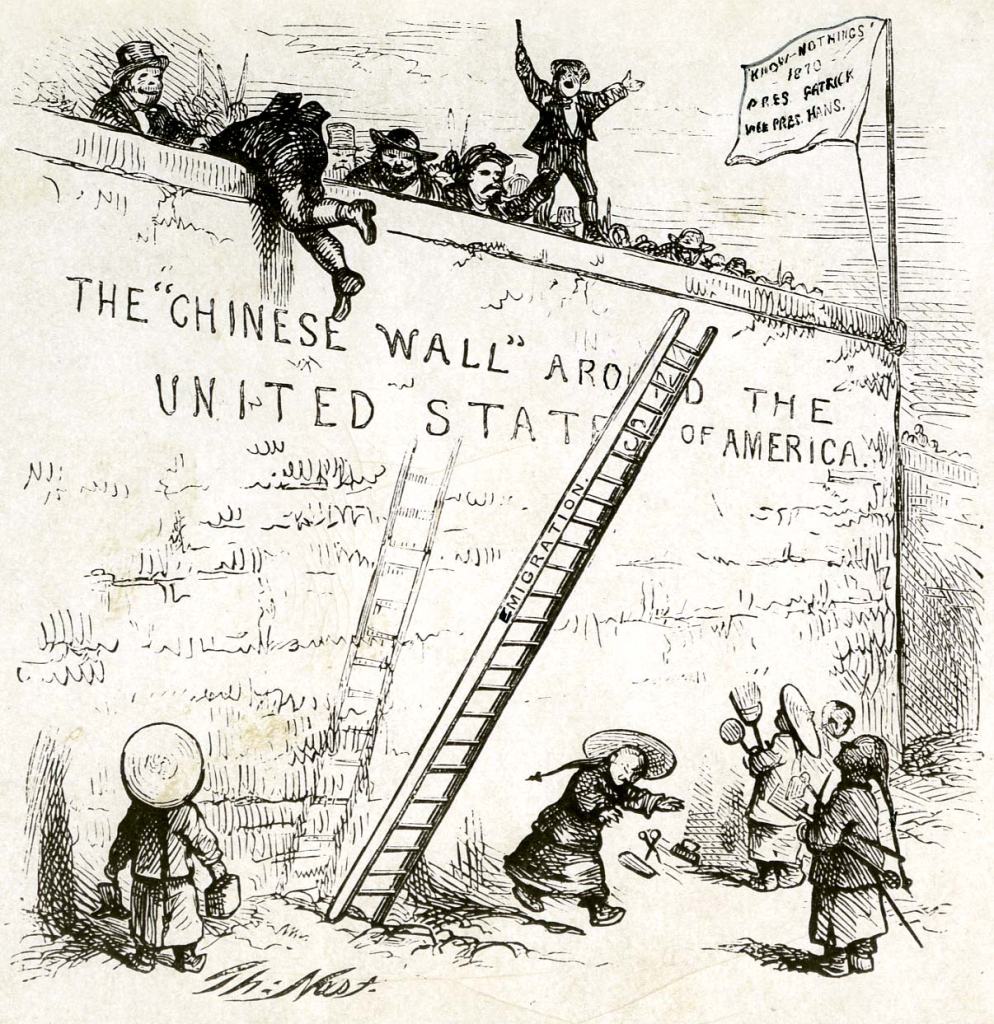

In 1905, construction of an “Immigration Station” began in the location known as “China Cove.” The facility, primarily a detention center, was created to control the influx of Chinese immigration into the country, because they were officially not welcomed with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed by the United States Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur. This act provided a 10-year temporary prohibition on Chinese labor immigration. Federal law prohibited the entry of an ethnic working group on the premise that it endangered the good order of certain localities. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 also placed new requirements on Chinese who had already entered the country. If they left the United States, for any reason, they were required to obtain certifications to re-enter the country. Furthermore, Congress refused State and Federal courts the right to grant citizenship to Chinese resident immigrants while these courts still had the ability to deport them.

Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.

According to Angel Island Conservancy, Chinese-Americans were one class of the Chinese that the U.S. could not keep out as they were already U.S. citizens by birth. This was due to having a father that was already a citizen. Until the mid-1920s, women could not have a separate citizenship from their husbands or their parents. A native-born woman could lose her citizenship by marrying a foreign national. Fortunately, back then, as it is currently, any person born in the U.S. is automatically a citizen, regardless of their parents citizenship status. Also, the children who were born of U.S. citizens are deemed citizens as well, regardless of where they were born. Therefore, any of the Chinese that could prove citizenship through their paternal lineage could not be denied entry to the United States.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was initially supposed to last for a decade. However, it was extended and expanded. The Angel Island Conservancy claims that by 1943 it was finally repealed when China became a U.S. ally in World War II. Unfortunately, following the repeal, Chinese immigration control was consolidated to the earlier 1924 Immigration Act that allowed only 105 Chinese immigrants into the U.S. each year. This also excluded classes of Chinese professionals and merchants. By 1965, this immigration quota system was abolished by the Immigration Act of 1965. The 1965 immigration act was also known as the Hart-Celler Act. It was passed by the 89th Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. This law abolished the National Origins Formula, which had been the primary basis for the U.S. immigration policy since the 1920s. The National Origins Formula was used between 1921 and 1965. It restricted immigration based on the existing proportions of the population.

Continue Reading: The Rise of Nativism: The Know-Nothing Party

Last edited April 22, 2021.

You must be logged in to post a comment.